Heritage Vehicle 3D Printing - Classic & Vintage Spare Parts

3D printed replacement parts and reverse‑engineered components for heritage and classic vehicles. Preserve originals and extend vehicle life with precision additive manufacturing.

The Heritage Vehicle Spares Parts Industry: Why It Exists and Why It Matters

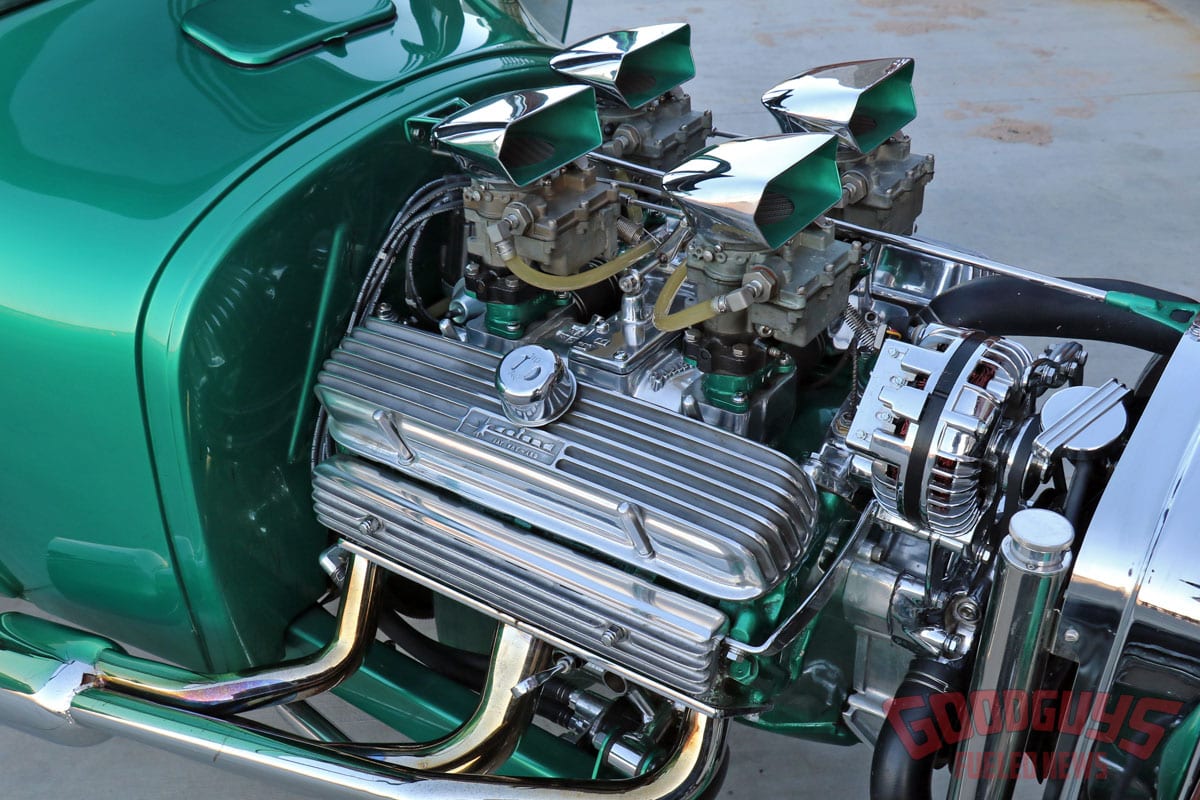

The heritage vehicle spares parts industry exists for one simple reason: history still moves. Classic cars, vintage motorcycles, steam engines, heritage rail vehicles, military vehicles, agricultural machinery, and historic commercial fleets were never designed to be museum pieces. They were built to work, to travel, to haul, to race, and to serve. Decades later, enthusiasts, collectors, museums, engineers, and preservation societies are still determined to keep them operational, authentic, and mechanically honest. That determination has given rise to an industry that sits at the intersection of engineering, craftsmanship, and historical stewardship. What makes this sector unique is that it does not benefit from scale. Original manufacturers no longer exist, tooling has long been scrapped, drawings are missing or incomplete, and supply chains vanished generations ago. Every single part becomes a problem to solve rather than a product to reorder.

Unlike modern automotive manufacturing, where components are produced in the millions and replaced wholesale, heritage spares are about continuity. Owners do not want “something that fits”; they want something that behaves as the original did, looks correct, lasts, and respects the vehicle’s provenance. That might mean reproducing a small nylon bush that controls a lever throw, a brittle Bakelite-style knob, a metal bracket that fractured from fatigue, or a once-injection-moulded clip that nobody has made since the 1960s. Each job is typically low volume, sometimes even a single unit, and often mission-critical. When one of these parts fails, an entire vehicle can be rendered unusable. That is the reality this industry addresses every day.

What also sets this sector apart is the emotional investment involved. Heritage vehicles are rarely just machines. They are personal projects, family heirlooms, community assets, or nationally significant artefacts. The spares industry therefore operates under a different set of pressures. Accuracy matters. Materials matter. Longevity matters. A poor reproduction does more harm than good, and word travels fast in tight-knit restoration circles. This is not a race to the bottom on price; it is a pursuit of correctness, reliability, and trust.

The Economic and Technical Challenges of Traditional Heritage Spares Manufacturing

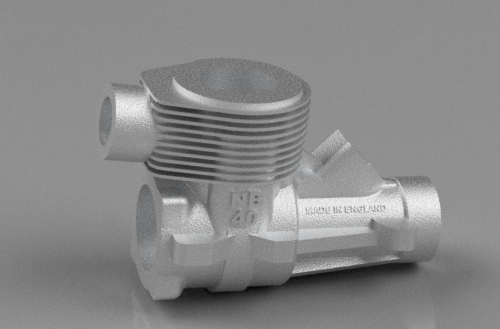

Traditionally, manufacturing spares for heritage vehicles has been an expensive and time-consuming affair. Injection moulding, die casting, stamping, and machining all require tooling, and tooling does not come cheap. For a small plastic component, the tooling alone can easily reach five figures before a single usable part exists. That might make sense if you are producing tens of thousands of units. It makes absolutely no sense when you need ten, five, or one. As a result, many parts simply never get remade. Vehicles are parked up not because the technology is complex, but because the economics no longer work.

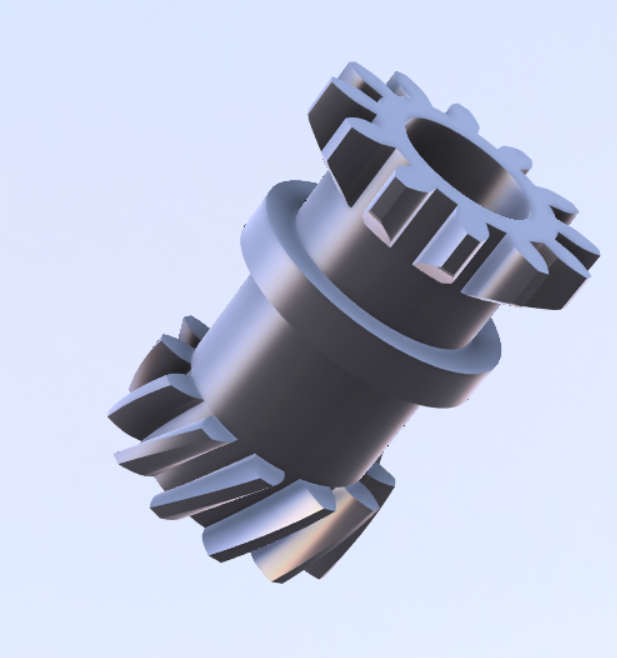

Machining can sometimes bridge that gap, but it brings its own limitations. Not every component was designed to be machined. Thin clips, internal geometries, snap-fit features, hollow sections, and organic forms can be extremely difficult or impossible to reproduce accurately using subtractive methods alone. Even when machining is feasible, the cost per unit can be prohibitive, particularly when skilled labour is required. Lead times stretch from weeks into months, sometimes longer, especially if the part has to be reverse-engineered from a worn or broken original.

There is also the issue of material availability. Many heritage components were produced using plastics and composites that are no longer manufactured, are environmentally restricted, or behave differently under modern processing methods. Engineers are often forced to make compromises, substituting materials that are “close enough” rather than correct. Over time, those compromises accumulate, and the vehicle drifts further away from its original mechanical character.

This is where the heritage spares industry has historically struggled. The demand exists, the skills exist, but the manufacturing methods have lagged behind the need. That gap is precisely where modern additive manufacturing—3D printing—has begun to prove its value.

Why 3D Printing Changes the Game for Heritage Spares

3D printing aligns almost perfectly with the realities of heritage spares work. It thrives on low volumes, complex geometries, and rapid iteration. Where traditional manufacturing demands commitment upfront, additive manufacturing allows parts to be produced directly from a digital model, with no tooling and minimal setup. That alone removes the single biggest barrier to reproducing obsolete components.

From a practical standpoint, 3D printing allows a damaged or incomplete part to be reverse-engineered, redesigned, and produced in days rather than months. A physical sample can be measured, scanned, or modelled in CAD, adjusted for known weaknesses, and improved where appropriate—all while retaining the original form and function. Once the model exists, it can be reproduced consistently, stored digitally, and modified if required. The part is no longer lost to time; it is preserved in data.

Material choice is another decisive advantage. Modern engineering filaments such as ABS, PETG, nylon, carbon-fibre-reinforced polymers, and high-temperature blends allow parts to be tailored to their working environment. A clip exposed to UV can be printed in a material that resists embrittlement. A load-bearing bracket can be printed at 100% infill for strength. A cosmetic component can prioritise surface finish and colour accuracy. These are decisions made at the design stage, not compromises imposed by tooling constraints.

Cost is where the impact becomes undeniable. When a part that would require thousands of pounds in tooling can be produced for a few hundred pounds—or less—the entire economics of heritage restoration shift. Vehicles that would otherwise be written off become viable again. Owners can justify repairs that previously made no financial sense. Small operators, museums, and volunteer groups gain access to manufacturing capability that was once reserved for large industrial players.

Strength, Durability, and Engineering Integrity in 3D Printed Parts

One of the most common misconceptions surrounding 3D printing is that printed parts are inherently weak. That assumption comes from exposure to hobby-grade prints made at low infill for speed and cost. In a professional context, particularly within the heritage spares industry, that approach simply does not apply. Strength is a design decision. Infill density, wall thickness, layer orientation, and material selection all play a role, and when they are chosen correctly, printed parts can meet or exceed the performance of the originals.

For functional heritage components—levers, clips, housings, guides, mounts—printing at high or full infill transforms the internal structure from a lightweight honeycomb into a solid mass. Combined with appropriate materials, this produces parts capable of withstanding repeated mechanical stress. In many cases, these parts are stronger than the originals because they benefit from decades of materials science advancement. That does not mean overengineering everything; it means understanding how the part is used and designing accordingly.

Durability also extends to environmental resistance. Older plastics were not designed with long-term UV exposure in mind, nor were they expected to last half a century. Modern alternatives such as PETG and advanced nylons offer improved resistance to sunlight, moisture, oils, and temperature variation. For heritage vehicles that are still used regularly—driven, displayed outdoors, or operated in working environments—this is a significant improvement that does not detract from authenticity.

Crucially, none of this requires guesswork. The iterative nature of 3D printing allows test parts to be produced, evaluated, adjusted, and refined before final production. That feedback loop is invaluable in heritage restoration, where no two vehicles are identical and wear patterns vary widely.

Preserving Heritage Through Digital Continuity

Perhaps the most profound benefit 3D printing brings to the heritage vehicle spares parts industry is digital preservation. Once a component has been modelled accurately in CAD, it is effectively immortal. It can be reproduced years later, shared securely, adapted for different variants, or scaled for alternative applications. This creates a living archive of parts that would otherwise disappear forever.

For clubs, museums, and restoration groups, this opens the door to collaboration on an entirely new level. A single successful reverse-engineering project can benefit dozens of vehicles worldwide. Instead of each owner solving the same problem independently, knowledge and data can be shared, reducing duplication of effort and cost. Over time, this builds resilience into the heritage ecosystem.

From my perspective, this is where 3D printing stops being just a manufacturing tool and becomes a preservation strategy. It allows us to respect the past while using the best tools available today. We are not replacing craftsmanship; we are supporting it. We are not altering history; we are ensuring it remains functional. That distinction matters, particularly in an industry where authenticity is everything.

FAQs

Is Heritage Vehicles suitable for outdoor use?

It depends on UV exposure and heat. Tell us the environment and we’ll advise the best material.

Can you print Heritage Vehicles for functional parts?

Yes. If you share the part purpose and any load/heat details, we’ll confirm the best settings and material choice.